No rushing for me. Bit tired, since you ask. Lots of weekend work in March and I am getting on a bit. Yes, I was in the room when G Keegan said that she’d have punched an Ofsted inspector who was rude. She’d got overexcited talking to 1000+ school leaders in a great big auditorium and mistook polite attentiveness for approval. The atmosphere sank to frosty after the remark, in a roomful of people who’ve devoted their lives to teaching young people the norms of civilised behaviour. We all have signs up in our reception areas asking people to be pleasant. All public servants are at the mercy of national anger at the moment so her offering to punch the regulator is – I can’t dress this up – a really bad thing to say. They report to her, for the love of God. Words fail me (apart from the preceding 150, that is).

Another conference’s post-match discussions were beset by people starting their remarks with ‘I’m going to be a bit provocative’. Let the hearer be the judge of that. You don’t know how wide might be the range of listener’s views on the matter. Your provocative may be tediously predictable to people who’ve put in the hard yards. I roll my eyes quietly.

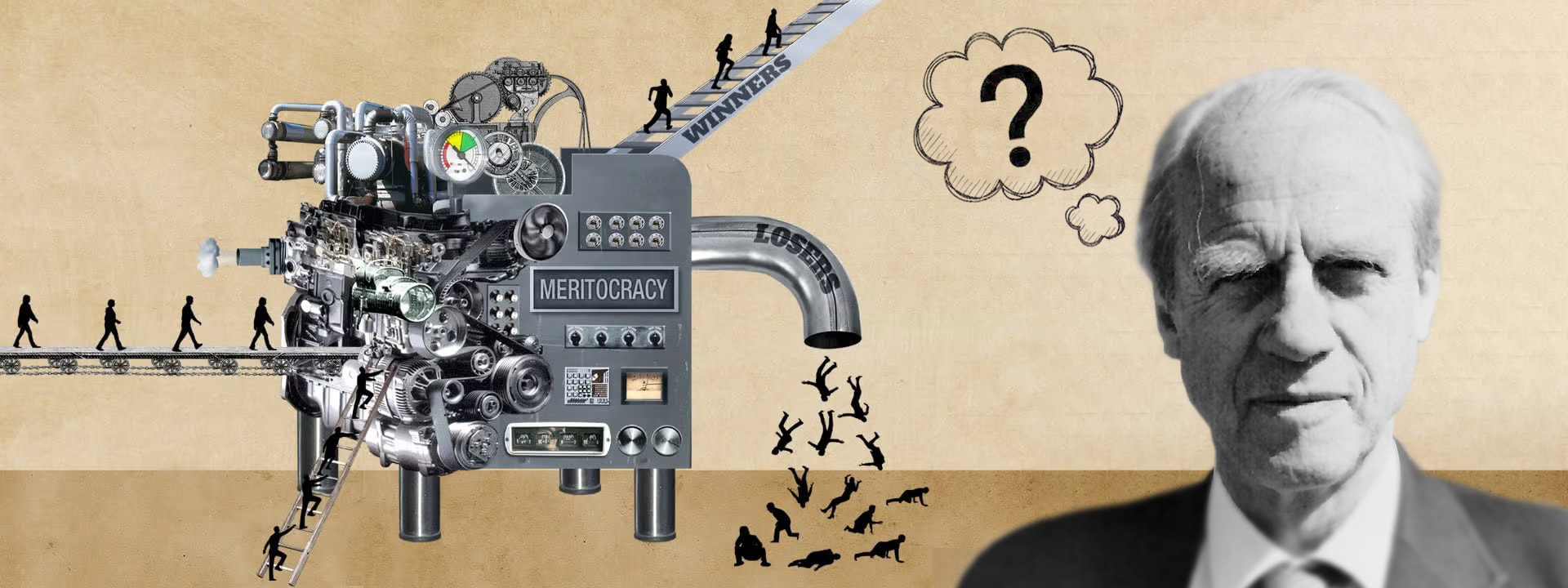

The actual speaker had been brilliant, posing a simple question: shouldn’t all schools be the same? What does it do to children and our system that we have local authority, comprehensive, grammars, faith, free, matted and so on. At the least, it means that central control is missing and admissions are a cat’s breakfast. Schools are enabled to do their own thing, or what they believe to be best, and children miss out. It’s a rare school that seeks out the least attractive children (by outcomes measures) and everyone misses out on the social vision of education as a model for a better world. Yes, sorting it out would be painful in one generation, but would be of immeasurable benefit for the rest. And yes, he’d manipulate admissions so that every school was genuinely comprehensive.

This glimmer of hope for a better society flickers in and out. Just when you think no one cares, or no one is willing to be bold, someone with all the facts, the research and the economics pops up and calmly revolutionises the future. Wouldn’t that be a great leap forwards?

The previous day I’d heard another good speaker who talked about bad leadership based on compliance, socialisation and internalisation. Stop me, I thought, that’s where we’re at. The Deliverance revolution of the Blair years brought easy-to-measure national targets. Teaching trimmed itself to meet those targets, so the purpose of schooling changed into compliance. A child at school taught that way could easily be a school leader now. Post 2010, the EBacc and other controversies have been constants and that young leader might well ask – ‘but hasn’t the Department always controlled the curriculum choices schools make?’ ‘Why bother with the arts, no-one’s measuring their uptake?’ Thus, compliant schools socialised the next generations and now that compliance is internalised to this narrow focus. Don’t say we don’t know what schools are for: we know very precisely.

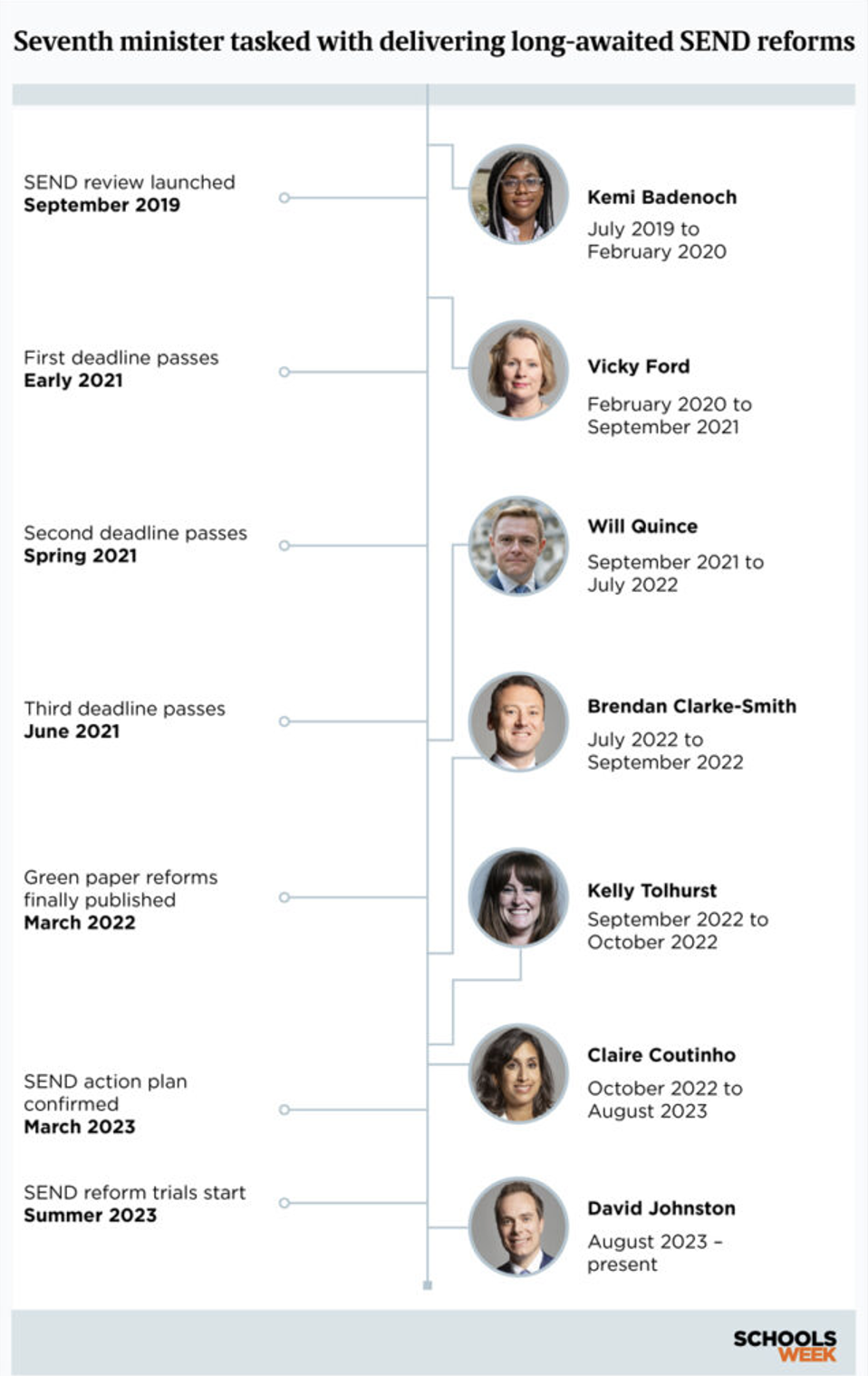

My biggest fear for the future of education is that poor-quality, short-term, politically-motivated thinking becomes ossified into structures that no one sees any more. So to return to the question: Why do we have so many different kinds of schools? Because we started mass education early and then had to fit the existing small and experimental systems into bigger ones. Church schools were absorbed in 1870 and again in 1944. Grammar schools carried on locally after the 1965 push to full comprehensives. City Technology Colleges and academies took control of schools away from local democracy deemed to be insufficiently responsive to children’s needs. Free schools came out of an ideology that parents would run schools better. All of these were – at best – sticking plasters on a system that needs recentring, like a navigation system that’s lost its satellite.

We need a school system that works for everyone, in schools that hold communities together and make them better places to live. As Harold Dent, Editor of the TES until 1950, said of the wartime plans:

A true democracy must be a community, united by a common purpose, bound by a common interest, and inspired by a common ethos. These ideals cannot be realised if from an early age children are segregated into mutually exclusive categories. All should be members of the one school, which should provide adequately for diversity of individual aptitudes and interests, yet unite all as members of a single community

Dent feared that a country without common schools might end up in discord and revolution. It was in everyone’s interest to make the fairest solution work. We didn’t, and we’ve got the discord. Might the time be now? I saw something that looked very like a unicorn here, last week. Surely we can summon up a better world if not for these children, then for the next ones along.

CR

22.3.24

RSS Feed

RSS Feed