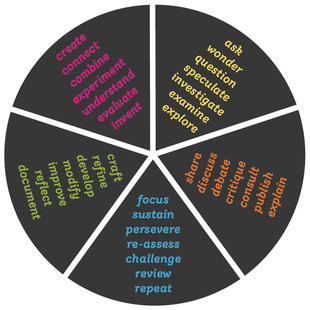

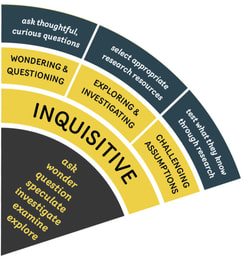

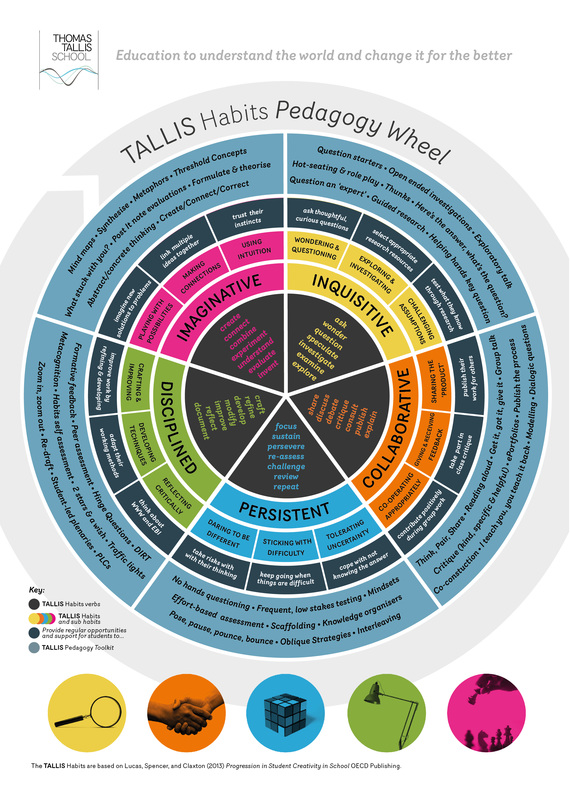

The TALLIS Habits Pedagogy WheelThe three cornerstones of our approach to teaching and learning at Tallis are: Threshold Concepts, Powerful Knowledge and Habits of Mind. The Wheel is intended to provide colleagues with an aide memoire for implementing Habits-related strategies in the classroom. It will feature on the cover of staff planners and be displayed as a poster in curriculum work areas. The wheel is divided into segments, building out from the centre, and beginning with the types of learning (verbs) explicitly supported by each of the Habits:

Next are the Habits themselves and their sub-Habits, followed by statements reflecting our intention to provide regular opportunities for students to strengthen their habits of mind:

|

| ||||||

The outer segments relate specifically to strategies teachers can employ that enable students to deliberately strengthen their habits of mind. We refer to this as the Tallis Pedagogy Toolkit. Some of these are well known and no doubt already familiar to you. Some were suggested by colleagues from across the curriculum at Tallis. Hopefully the list of strategies will support and extend the development of your own pedagogical toolkit. The Toolkit was inspired by Rooty Hill High School's Creativity Wheel and Tom Sherrington's Pedagogy Postcard series. The following list is intended to provide further guidance about the strategies referred to on the wheel, along with links to additional resources:

TALLIS Pedagogy Toolkit

Inquisitive:

|

Question starters - Typically, teachers give information and then ask questions about it. Hearing the question first, especially a great one, radically increases the need to learn the information just to find the answer. Questions, used strategically at the start of lessons or new schemes of work, can be powerful motivators. They can place students in the role of detective, searching for clues to solve an investigation. Open questions are the kind that lead to multiple (and sometimes contradictory or debatable) responses. Teachers ask lots of questions, the vast majority of them procedural. A carefully formulated and compelling question, which might be displayed prominently before the lesson has begun, can focus a whole class and stimulate a need for learning. Great questions are able to challenge beliefs and misconceptions and might be closely related to your subject's Threshold Concepts. Consider also the power of student-generated questions. See also 'Here's the answer, what's the question?' below.

|

|

Open ended investigations - Assignments that are genuinely open ended require students to wonder, question, explore and investigate. However, such investigations need to be supported in various ways. For example, there should be some sense of a minimum expectation, a simple guide, a clear timescale and possibly even a great example. Extended Learning Enquiries, at their best, can inspire amazing levels of engagement, pride and excitement. But if they're not well designed, they can lead to mediocre work and very little learning.

|

|

Exploratory talk - Discussion can be a way for groups of students to explore a new idea or even debate a misconception. Exploratory talk is designed to encourage pupils to listen critically but constructively to each other's ideas. Talk like this needs to be well-structured and operate with agreed rules. For example: everyone listens actively • people ask questions • people share relevant information • ideas may be challenged • reasons are given for challenges • contributions build on what has gone before • everyone is encouraged to contribute • ideas and opinions are treated with respect • there is an atmosphere of trust • there is a sense of shared purpose • the group seeks agreement for joint decisions.

|

|

Hot-seating and role-play - Typically used in Drama and English lessons but applicable across the curriculum, hot seating is a technique whereby students are asked to occupy the 'seat' of a character and then quizzed by other members of the class. They answer these questions 'in role'. This encourages all participants to imagine a different viewpoint to their own, developing empathy and imagination (what an ex student once described as "wonderation"). How would this technique work beyond the language arts? How and why might you hot seat someone in the news, a historical or religious figure? Would it be possible to hot-seat a molecule or imagine the views of a decimal point?

|

|

'Thunks' - Some seemingly simple questions have the power to stop you in your tracks and make your brain go "Ouch!". For example, "Can you feel guilty for something you haven't done?" A Thunk can function as a mental warm-up, a way to get the brain working a bit harder. It can make an excellent starter for a lesson or be used to generate a cognitive gear change mid lesson. Whilst there are no right or wrong answers to Thunks, students should be required to justify their responses.

|

|

Here's the answer, what's the question? - This is a simple activity designed to reverse engineer the usual process of question and answer. Instead of asking a question, the teacher or student provides an answer and others guess the question. For example, if the answer is 49, what's the question? If the answer is tragedy, what's the question? Often there is more than one possible question, so students should be required to justify their choices. Which is the best question?

|

|

|

Question an 'expert' - Schools are full of experts so, if possible, why not recruit an expert to visit your class to be questioned directly by the students? Experts might also be found from amongst parents/carers and in the local community. If they can't physically visit the school, consider setting up a Skype session. Even asking students to imagine what questions they would ask an expert on a particular topic (whether or not one is actually available) can be a very revealing exercise. For example, "What would you ask Picasso about this painting if he was sitting next to you?" Another approach involves using the Mantle of the Expert. Linked to hot-seating and role-play, students are asked to imagine that they are experts in a particular field. They research the area of expertise, put on the mantle (archeologist, forensic scientist, military historian etc.) and work accordingly. Students might then quiz each other about their roles, responsibilities and discoveries.

|

|

Guided research - Often associated with graduate and post-graduate level study, guided research is similar to open-ended investigations in the sense that it allows a student to pursue an area of study that may lie beyond the scope of the 'normal' or prescribed curriculum. An example of this might be the Extended Project Qualification undertaken by some Post 16 students. The phrase also describes the need for students to be given guidance about how to conduct strategic research (rather than simply typing a phrase into Google and hoping for the best). Students should be taught how to use the library, how to use an index, how to get the most from an online search engine, what to trust online and what to treat with suspicion etc.

|

|

Helping hands key question - This strategy is used by colleagues in Design Technology. Students are given a picture of a hand printed on card. When they want to ask a question they must give the card to the teacher. They are then unable to ask any further questions in the specified time frame. Students are therefore required to think very carefully about their chosen question so as not to 'waste' the opportunity. This technique leads to much more strategic thinking and active listening, since students must pay attention to others' questions and plan their own carefully.

|

Collaborative:

|

Think, Pair, Share - Students need many opportunities to talk in a linguistically rich environment. In sharing their ideas, students can take ownership of their learning and negotiate meanings. It works like this:

|

|

Reading aloud - Reading aloud is crucial to language development in the early years but can also have significant benefits for older students. Language comes to life when read aloud and shared with others. Oracy is the foundation of literacy. Being read to can be a magical experience. It takes practice and skill. It requires active listening. It is community building. Whether it's the teacher reading from a novel 'in character' or the collaborative class reading of a play, the recitation of poetry, the exploration of a historical source or students reading their own writing to the rest of the class, reading aloud should have an important place in the day to day life of young people.

|

|

Get it, got it, give it - This strategy was suggested by colleagues in Maths. All students in class tackle a new topic or idea. Those that have "got it" then move around the class giving advice to other students. It is a form of peer mentoring which encourages collaboration through the sharing of student expertise.

|

|

Group talk - Group work and talking in groups used to be almost a required feature of an "outstanding" lesson. More recently, the efficacy of group work and talk has been questioned. Activities done in groups can be transformational or they can simply give the illusion that work is being done but very little learning is really taking place. Like most activities in the classroom, group work and talk needs to be well planned and have a clear justification. The arrangement of the group(s), the ground rules, the purpose of the talk (which needs to be shared), the students' roles and responsibilities, the success criteria and your role as the teacher all need to be carefully worked out. Thankfully, there are lots of ways of organising groups talk from Talking (& Listening) Triads to the Jigsaw Method. The most significant benefit of well-planned group talk is a way for students to use the knowledge that they have acquired, dredging up information from their long term memories and putting it to some use. Learning in groups also allows you, the teacher, to observe whether or not your students have learned enough of what they need and whether pesky misconceptions are still currency. This allows you to make targeted interventions more effectively.

|

|

Critique (kind, specific & helpful) - Critique is a form of structured peer feedback. It features in Ron Berger's book 'An Ethic of Excellence' and is exemplified by the now famous Austin's Butterfly. Critique is essential to Berger's plea for increased levels of discipline in the crafting and improving of students' work. The process has rules, is structured and supports the development of refined outcomes. Given that young people give each other feedback all the time, much of it wrong, the process of critique needs to be taught and practiced to become really effective. Berger outlines a number of key principles:

|

|

ePortfolios - An electronic portfolio enables students to generate evidence of their learning using a variety of web based presentation tools. The advantages of an ePortfolio over conventional paper based documents are:

|

|

Publish the process - There are many reasons why it's important to share work in progress (rather than just the finished outcome) and a range of strategies for doing so. Students need models from which to work and those that reveal how they have been made are most useful. Sharing incomplete projects helps to demystify the learning process. Learning is often a messy business and the process of crafting and improving should be celebrated. Students benefit from seeing how something sophisticated can be constructed from multiple steps. Misconceptions can be tackled by sharing wrong turns and dead ends, since these are likely to have been encountered by all students at some point. Celebrating the process of learning something new highlights the need to develop good habits and a growth mindset. You could experiment with publishing the process by: creating a wall display of work in draft • sharing work in process on a blog or website for others to comment on • beginning a lesson with an incomplete piece of work and asking students to offer suggestions for next steps and/or improvements etc.

|

|

Co-construction - Co-construction places a greater responsibility on the student to engage with the process of learning and teaching. It is not meant to undermine the teacher's role but to provide opportunities for greater metacognition. Students who are engaged in co-construction must consider not only what but how a new idea might be best tackled and understood. The aims of co-construction in education are:

|

|

I teach you, you teach it back - Closely linked to co-construction, this strategy is a tried and tested way for students to reinforce their own understanding by formulating a lesson for others. Students are taught something. They are then required to teach it to another student. The teacher can observe the process in order to see which concepts have been grasped fully, whether misconceptions are getting in the way and where there might be gaps in the student's understanding.

|

|

Modelling - Teachers use models for different purposes. A model of excellence (an example of a fine piece of work) can help to establish a benchmark or target. Ron Berger describes many examples of these models in his book 'An Ethic of Excellence'. Students need to understand what excellent looks like. Secondly, students also need models of how to get there (this is sometimes referred to as scaffolding). This may involve a demonstration of a sequence of steps. A diagram, flow chart or list can work well, depending on the assignment. Of course, teachers model attitudes, behaviours, competencies, mindsets and values too! See also 'Scaffolding'.

|

|

Dialogic questions - Dialogic talk is a strategy that moves beyond the call and response, question and answer routines of some classrooms. It aims to develop:

|

Persistent:

|

No hands questioning - Instead of asking for students to put their hands up in response to a question, teachers target particular questions at particular students, calling them by name. There are two main advantages to this technique:

|

|

Frequent, low stakes testing - We might assume that the function of testing is to assess students' performance. Have they learned what we wanted them to know? However, some research suggests that frequent, low stakes tests can also help students learn. Testing and re-testing aids retrieval and retention of information (better than just studying). "Frequent" could even mean every lesson for a few minutes. Testing can also improve the transfer of knowledge to new contexts. There's even the suggestion that testing can help students remember things that weren't even tested! Lots of small tests of material (that has just been studied) seems to be a far more efficient process of knowledge building than big, infrequent tests preceded by lots of cramming.

|

|

Mindsets - Carol Dweck's psychological research, resulting in her Mindset theory, proposes the relatively simple idea that it is what someone believes about his or her own intelligence that will determine how s/he approaches a problem or a setback. A Growth Mindset is preferable to a Fixed Mindset. Encouraging students to accept the notion that intelligence is flexible, expandable and adaptable, like a muscle that strengthens with deliberate practice, can have a dramatic effect not only on performance but also on self-esteem. This isn't just about effort. Effort needs to have a focus. The idea has its critics. However, used cautiously, mindset theory can pave the way for discussions with students about the relationship between attitudes and the capacity to learn.

|

|

Effort-based assessment - Linked to the development of a Growth Mindset (see above), assessment is focused on the amount of effort the student has used to reach a particular learning goal rather than assessment being linked to performance. As Dweck and others are keen to point out, effort alone is no guarantee that learning is taking place and a specific challenge or target should always be the focus of the effort. Effort-based assessment should be used strategically to explicitly support the development of students' persistence. Part of our assessment strategy at KS3, for example, is to assess students' effort towards the development of their Habits of Mind. Students' self-assessment should be an important part of the process.

|

|

Scaffolding - In the early stages of learning a new skill or concept, students benefit from structured support. This is often referred to as scaffolding. Scaffolding might take several different forms: teacher modelling, sequences of tasks, templates and guides, exemplar outcomes etc. Scaffolding helps prevent the situation where a student feels that the task is beyond them and so gives up too early. It can also stretch and challenge a student who might be tempted to complete the task too quickly or be unclear about the level of response required for success. Scaffolding is linked to Vygotsky's notion of the zone of proximal development. The teacher provides some form of scaffolding to move the student from what is not known to what is known. Just like scaffolding on a building, support is gradually removed as the student gains in confidence and 'mastery' of the new knowledge. See also 'Modelling'.

|

|

Knowledge organisers - Knowledge Organisers (sometimes known as Learning Mats) attempt to specify and visually organise a specific body of knowledge in reduced form on a single page. They can help teachers decide what exactly they want their students to know. They support students in making explicit what has been learned, what needs to be remembered and provide a handy resource for revision. In subjects where students need to know a large amount of information, Knowledge Organisers, if used frequently and linked to similarly frequent, low or no stakes testing arrangement, can help to move knowledge from the short to the long term memory, thus supporting the development of 'mastery'. A similar type of single page resource can be used to support literacy across the curriculum and a subject's Threshold Concepts, for example. See also 'PLCs' and 'Threshold Concepts'.

|

|

Pose, pause, pounce, bounce - This is a refinement of the no hands questioning strategy. The process is relatively straightforward:

|

|

Oblique strategies - Oblique Strategies (subtitled Over One Hundred Worthwhile Dilemmas) is a set of cards, created by Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt, used to break deadlocks in creative situations. Each card contains a (sometimes cryptic) remark that can help resolve a creative dilemma. For example: • Use an old idea • State the problem in words as clearly as possible • Only one element of each kind • What would your closest friend do? • What to increase? What to reduce? • Are there sections? Consider transitions • Honour thy error as a hidden intention • Ask your body • Work at a different speed. The idea is to come at the problem from an unusual (oblique) angle, taking it, and your brain's conventional ways of thinking, by surprise. Various web-based versions of the cards are available. You may wish to create your own Oblique Strategies suitable for your discipline/classroom.

|

|

Interleaving - Conventional wisdom might suggest that in order to learn something complex we should attempt to subdivide the skills required and practice them one at a time in sequence (AAA, BBB, CCC etc.) This might be called 'blocking'. However, research in cognitive psychology now suggests that we might approach the challenge differently, interleaving the various components (ABC, ABC, ABC etc.) The technique seems to work particularly well in maths where the interleaving of component parts of new knowledge reduces the risk of rote responses. Rather than rehearsed answers, the brain must continually focus on searching for different solutions. There is some evidence that interleaving requires some prior knowledge with the material being studied to work effectively. Where students are tackling a completely new and complex task (e.g. learning a new foreign language, for example) interleaving might have little, no or even negative effects, leading to greater confusion. Clearly, interleaving does not suit all subjects or all topics. However, the basic message is that mixing things up in your teaching can have positive effects in the longer term for students, helping to move knowledge from short to long term memory.

|

Disciplined:

|

Formative feedback - The goal of formative assessment is to monitor student learning to provide ongoing feedback. Formative assessments:

|

|

Peer assessment - Formative peer assessment can be a powerful tool for developing students' responses to a particular assignment. The process is straightforward but benefits from a culture of peer assessment having been established in the classroom. Students provide suggestions to each other about how work can be improved. This has benefits for both the receiver and the giver of the feedback. See also 'Critique'.

|

|

Hinge questions - A hinge question is a diagnostic tool for assessing understanding at a significant point in a lesson. It has two inter-linked meanings:

|

|

DIRT - Directed Improvement and Reflection Time is a strategy designed to get students to focus on crafting and improving their work. DIRT enables students to respond to feedback given by the teacher. The temptation is to try to mark everything. This is not only impossible to sustain but relatively useless as a strategy for improving the quality of students' work. A more sensible strategy is to think of marking as feedback and make sure there is enough time in your lessons for students to do something with the feedback you have given them about a specific piece of work. Don't be afraid to dedicate significant time in your lessons for DIRT. "If it isn't excellent, it isn't finished." See also 'Re-draft' and 'Critique'.

|

|

Metacognition - This contribution to the Toolkit came from colleagues in Science. CASE (Cognitive Acceleration through Science Education) lessons in Year 7 and 8 involve the students tackling demanding problem: e.g. What is the mathematics behind a balance beam balancing? When is it best to use the concept of a median average rather than a mean? Why are graphs useful? How can they be used? At the end of a CASE lesson the students have to reflect formally in writing on what they’ve learned in the lesson for 5 minutes. They do so in silence. The work isn’t marked, although students are encouraged to share their responses with the others. The teacher will circulate to judge from the students' responses how their learning in the thinking skill has progressed. After every thinking lesson the students are asked are the same 5 questions: At first I thought that ... Then I realised that ... I had a problem with ... It got better when ... If I did this in a group again I would...

|

|

Habits self-assessment - It is important to provide students with opportunities to assess their own strengths and areas for improvement relating to the Tallis Habits. One simple strategy is to use the Tallis Habits Wheel. Students shade in segments of the wheel, returning later to assess whether or not particular habits and sub habits have strengthened. A technique like this can bookend a project or scheme of work. Students may also have an opportunity to regularly assess their habits by using the Tallis Habits web app.

|

|

2 stars & a wish - This is a simple strategy to enhance peer assessment. Students identify two positive aspects of the work of a classmate and then express a wish about what s/he might do next time in order to improve another aspect of the work. Teachers model the strategy several times, using samples of student work, before asking the students to use the strategy in pairs on their own. They check the process and ask pairs who have implemented the strategy successfully to demonstrate it to the whole group.

|

|

Traffic lights - A Red, Amber, Green traffic lights system is a simple strategy for indicating understanding and enhancing formative self-assessment. Students can display the relevant colour card to alert teachers about their current need for support: Green - I understand this well; Amber - I need a bit of support; Red - I don't understand and need help. Students might also use this system when working collaboratively to indicate the collective understanding of the group. The process allows the teacher to circulate whilst students are working and see quickly where support is required without students having to stop working to request help. A RAG system can also be linked to summative teacher feedback, often referred to as RAG rating.

|

|

Zoom in, zoom out - This technique encourages students (and teachers) to compare the skills needed for learning to the techniques used in the creation of films. Film directors use the camera to zoom in and out for specific reasons. Students also need to be able to balance the need for close-up analysis of material with a wide angle view. David Didau sees a parallel with Bloom's taxonomy. Zooming in enables close analysis - identify, explaining, exploring and analysing. Zooming out is about seeing the big picture - evaluating and creating.

|

|

Re-draft - The process of drafting and re-drafting a piece of writing (perhaps several times) supports students' abilities to craft, develop, refine and improve, responding to teacher feedback. It may be one of the processes used in DIRT (Directed Improvement and Reflection Time) and should more than simply copying up into 'best'. The purpose of re-drafting is one of iterative improvement. This might mean cutting back or pruning as well as making additions and enhancements. It will inevitably involve correcting for accuracy of spelling, punctuation, grammar but also correcting misconceptions or wrong turns. It requires the writer to view his or her work from the point of view of the reader.

|

|

Student-led plenaries - This is a simple strategy for evaluating levels of understanding. One or more students are asked to summarise the key take-aways from the lesson. This can be a simple summing up lasting a few moments or more complex, perhaps a whole lesson being dedicated to students working together in themed groups, summarising the content and key ideas of a whole scheme of work. See also 'What stuck with you?'

|

|

PLCs - A Personal Learning Checklist is a tool for students and teachers to monitor learning. There are two main types:

|

Imaginative:

|

Mind maps - Mind maps are graphic representations of a set of connected ideas. They enable teachers and students to organise visually a complex subject. There are five essential characteristics of mind maps:

|

|

Synthesise - Synthesising, a step on from summarising, involves combining separate ideas into a coherent whole. Synthesis is a higher order skill, the creation of a kind of mosaic, greater than the sum of its parts. In philosophical terms, synthesis is the outcome of dialectical thinking whereby a thesis is contradicted by its antithesis, leading to the creation of a synthesis. Encouraging students to develop a theory, imagine criticisms of that theory and identify common truths in the formation of a new proposition promotes synthetic thought. See also 'Formulate & theorise'.

|

|

Metaphors - Everyday language is filled with figures of speech (metaphors and similes). Often, metaphorical language connects a relatively abstract idea (life, death, love etc.) to something more concrete. One is directly associated with the other as in the phrase "All the world's a stage" from Shakespeare 'As You Like It'. A direct comparison is made between life and acting, a rich and complex direct comparison which causes us to reflect deeply on all the possible connections. Metaphorical learning is therefore the deliberate encouragement of this type of associative thinking. See also 'Abstract/concrete thinking'.

|

|

Threshold Concepts - Threshold Concepts are the BIG IDEAS that will help students develop a deeper understanding of a particular discipline. They are not meant to be instantly understood. Once opened, they introduce students to troublesome knowledge; a new way of seeing the subject they are studying. Threshold Concepts have particular characteristics. They are:

For the teacher, Threshold Concepts provide a structure upon which to design the curriculum, identifying the foundational knowledge and skills that underpin the discipline and reducing the risk of content overload. |

|

|

What stuck with you? - This strategy can be used in a number of ways but works well as an end of lesson or topic activity. Students are each given a Post It note and asked to write/draw the idea, fact or concept that they will take away. These can be displayed on the door of the classroom (or somewhere equally prominent) and used as the starter for the next lesson, making explicit prior knowledge. These are also referred to as Exit Tickets. An alternative might be to ask students to write one question they would still like the answer to.

|

|

Post it note evaluations - The ability to identify and communicate an idea as concisely and precisely as possible is a skill that is tested in this strategy. Students are given a Post It note (or equally small piece of paper) and asked to write an evaluation of their work (this could take the form of What Worked Well and Even Better If, for example). This is meant to be a quick activity, perhaps done at the end of a lesson or at a 'hinge' moment in the lesson. There is no room for waffle!

|

|

Formulate & theorise - The word formulate means to "make from scratch", to take raw material and form it into something new. Reflecting the scientific method, this strategy asks students to assess available information in order to develop an hypothesis, to conjecture and theorise. This supports the work of the imagination, making connections and playing with possibilities.

|

|

Abstract/concrete thinking - Tom Sherrington describes the "tipping point" in many subjects "when the learning moves beyond the territory of tangible ideas, objects and observable phenomena into the realm of the abstract. Taking students across this divide is a key aspect of enabling them to access higher level learning." Teachers must make decisions about when to zoom in and zoom out, when the micro is better than the macro, when knowing and understanding a technical phrase like Depth of Field is useful, rather than simply observing its effects. We should be in the business of building powerful knowledge, cognitively superior to the everyday wisdom brought from home, and this requires teachers to be explicit about the connections between the concrete and the abstract. See also 'Zoom in, zoom out' and 'Threshold Concepts'.

|

|

Create/connect/correct - This phrase describes the iterative cycle of Design Thinking. This approach can be used by students to solve problems of all kinds. The full cycle of activities can also be described as follows: Discovery, Interpretation, Ideation, Experimentation, Evolution. The process is similar to other models such as TASC (Thinking Actively in a Social Context): Gather/Organise, Identify, Generate, Decide, Implement, Evaluate, Communicate, Learn from experience. Designers solve real world problems using an iterative process of crafting and improving based on constant feedback. The skills used by designers (in a wide variety of fields - architecture, engineering, product design, medicine etc.) can also have great benefits for students in the classroom. See also 'DIRT', 'Oblique Strategies' and 'Open-ended investigations'.

|

Colleagues may wish to use this form to help them plan the implementation of their Tallis habits Pedagogy:

|

| ||||||||||||